The History of Bristol to 1497

Located in the southwest, Bristol was not only one of the busiest trading seaports in England but also one of the wealthiest towns in the county of Somerset during late medieval times. It played a vital role in shaping the course of events leading up to John Cabot's discovery of the 'new founde landes.' What factors made Bristol such an important and influential 15th century port, even when England was still only a minor European power? Moreover, why was Bristol Cabot's best choice – even over pivotal Spanish and Italian ports? While Bristol probably would have continued to thrive as a seaport after the close of the middle ages, it was Cabot's success which sparked other adventurers to undertake similar explorations and which made Bristol's name famous throughout history.

History and Origins

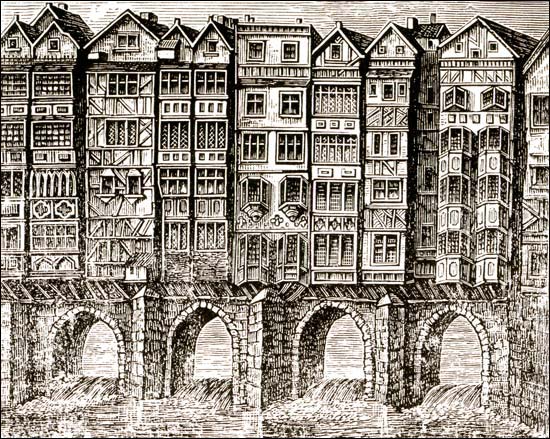

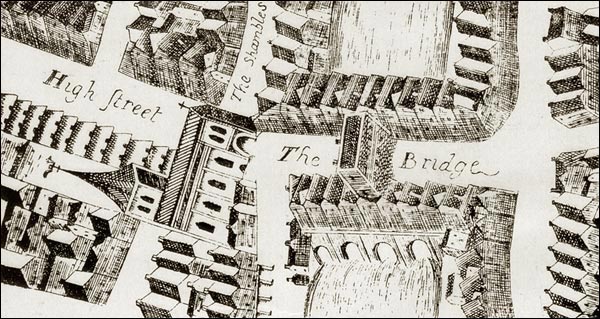

Although many English towns can definitively trace their roots back to the invasions of the early Romans around 43 AD, the history of Bristol is not as clear. The earliest recorded place-name for the area dates only as far back as the mid-11th century. Brygestowe, as it was called, simply meant 'the place of assembly by the bridge.' By the 15th century, Bristol was generally both spelled and pronounced 'Bristowe' (Walker 5; Morison 161).

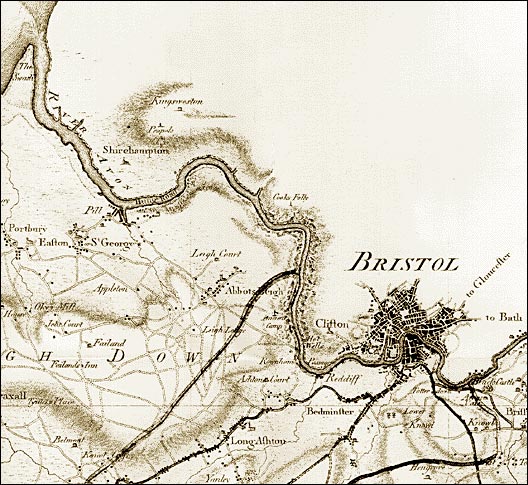

It is traditionally thought that the borough of Bristol was originally established by the Anglo-Saxons at the loop where the Avon River meets the Frome. Sometime during the early Middle Ages, they had selected the small peninsula located at the junction of these two rivers. Upon this site they constructed a bridge across the Avon and a surrounding town (Morison 161).

Historians generally believe that the town was fairly prosperous during its early years. This assumption has been reinforced by archaeological evidence that clearly shows coins were struck at a mint at Bristol from the reign of Cnut (1016-1035), and perhaps as early as King Erhelred Unraed's reign (978-1016). A further indication of Bristol's growth during the Middle Ages is found in the Domesday Book, a huge survey of landholdings compiled by King William the Conqueror from his 1086 census. The book recorded Bristol as next in size after London, York and Winchester (Walker 5; Wilson 45).

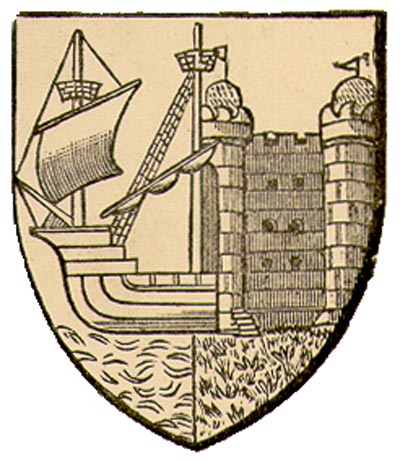

William the Conqueror (1066-1087) gave Bristol its own mint – an indication of its importance and wealth even in medieval times – and built a motte and bailey castle which rivalled the Tower of London.

Some sense of Bristol's real nature as a seaport during these early years is derived from a statement by King Stephen, a Norman who ruled in the middle of the 12th century. He described the town as:

nearly the richest of all cities of the country, receiving merchandise by sailing vessels from foreign countries; placed in the most fruitful part of England, and by the very situation of the place the best defended of all the cities of England (Wilson 45).

Economy

Much of Bristol's early importance rested upon its wool trade with Ireland. It has been estimated that by the 15th century, Ireland provided a market for at least one third of the cloth exported from Bristol. In return, it received merchandise nearly double the value: corn, linen, timber, cattle and fish which was a staple food in the English diet. As the superior quality of English wool became known throughout Europe, Bristol's trade expanded to encompass the Baltic (Carus-Wilson 2, 3; Kemp 110).

The town began to prosper from 1247, when the Frome River was diverted by way of the Severn. In 1373 it was granted a charter and county status which widened Bristol's trade to include business with Portugal, Spain, the Mediterranean and Iceland ("About Bristol/Title Page").

The greatness of Bristol rested on an economy which centred around inland and overseas trade. Goods poured in from the many English towns including Chester, Milford Haven, London and Plymouth. The burden of transportation was lessened by the close proximity of rivers like the Severn and Avon. This relatively efficient system of waterways allowed agricultural produce, iron, timber, cloth, wool, fish, and tin to be easily shipped from throughout England into Bristol's harbour and from there on to Ireland, northern Europe, France and Spain. In exchange, Bristol imported goods such as wine, spices and olive oil (Carsus-Wilson 1; Williams 16).

Second in importance only to London, Bristol had a number of advantages over many other English seaports of the time. The exceptionally high tides of up to fifty feet permitted vessels to rapidly travel through the narrow wooded gorge of the Avon River into Bristol's sheltered harbour which protected ships from invasions by foreigners and pirates (Carsus-Wilson 2).

The town's paramount location, along with its strong tradition as a centre of European trade, contributed to its attractiveness for merchants and mariners. Thus once Cabot's eye had turned towards England, the westward facing Atlantic port of Bristol must have seemed like an obvious choice.