Beaumont Hamel: July 1, 1916

Of all the battles that the Newfoundland Regiment fought during the First World War, none was as devastating or as defining as the first day of the Battle of the Somme. The Regiment's tragic advance at Beaumont Hamel on the morning of July 1, 1916 became an enduring symbol of its valour and of its terrible wartime sacrifices. The events of that day were forever seared into the cultural memory of the Newfoundland and Labrador people.

The Plan

The Somme offensive had its origins in Anglo-French plans to bring hostilities to a rapid close. At the end of 1915 the war was going badly for the Allies. The Gallipoli campaign had been a failure. The Eastern Front was in disarray and the Western Front was locked in a stalemate. Germany had marched through Belgium and into northern France, where its army was securely entrenched near the River Somme. British and French forces desperately needed a success. Commanders spent the winter of 1916 developing a major offensive to regain control of the Somme.

But their plans were upset when Germany launched a massive attack against French forces near Verdun (a city in northeast France) on February 21, 1916. The battle lasted for almost 10 months and siphoned off many of the French troops originally intended for the Somme offensive. In consequence, the Battle of the Somme became a largely British effort, designed to relieve beleaguered French troops at Verdun, and to cause a decisive breakthrough in the German lines.

Courtesy of the Imperial War Museums, (©IWM, Q 23760), London England. http://www.iwm.org.uk/history/the-battle-of-verdun

The Newfoundland Regiment, still with the 88th Brigade of the 29th Division, received word on February 25, 1916 that it would be part of the Somme offensive. It departed Egypt on March 14, 1916 and arrived at France eight days later. For the next three months, it readied for combat. The men trained rigorously, did tours of duty on the front line, dug trenches, strengthened defences, and observed the enemy.

Although the battle would not begin until July 1, the months leading up to it were dangerous. The Germans often shelled Allied trenches, and snipers were another threat. On April 24, the Regiment sustained five casualties when German bullets wounded four men and killed Private George Curnew. He was 19 years old. More casualties followed in the coming weeks.

Battle Approaches

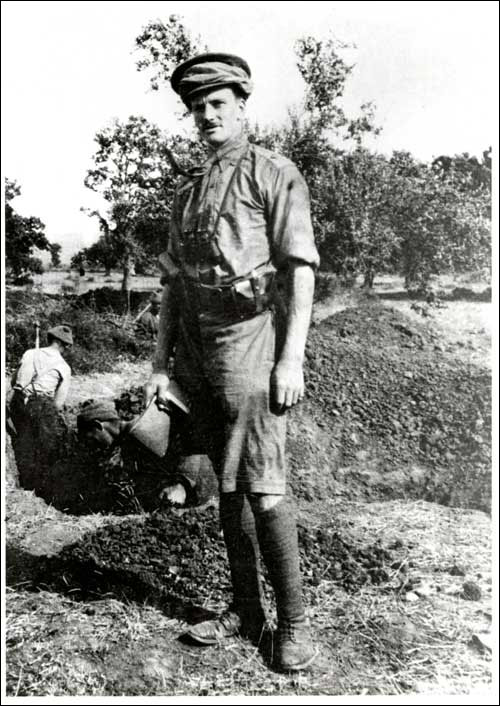

As the date of the battle approached, the men of the Newfoundland Regiment grew apprehensive. "There seems to be a strange pensiveness about everything and we are all strangely thoughtful about the 'Great Push'," Lieutenant Owen Steele wrote in his diary on June 20.

Yet he also expressed a confidence in the strength of the Allied forces and found comfort in a shared sense of purpose and duty. "Everyone seems so cool about it all, quietly preparing for what is going to be the greatest attack in the history of the world, and very possibly the greatest there will ever be," he wrote on June 23. "We only hope that it may be a very strong factor in bringing an early end to the war."

Courtesy of Archives and Special Collections (Coll. 179 1.01), QE II Library, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John's, NL.

Many soldiers sent reassuring letters home in the days before the battle, although censorship laws prohibited them from saying anything about the Allies' plans. "This letter will be very short for we have been up to our eyes in work for the past fortnight and will be for some time to come, the reason for which I cannot give you even an inkling; but you will have heard all before this reaches you," Steele wrote to his parents on June 25. "Am afraid that quite a long time will elapse before you get another letter from us, but you need not worry for we shall be all right."

Private Francis Lind's letter to the Daily News on June 29 was filled with reassuring bravado, which masked any anxiety or fear he may have had: "No pen could describe what it is like, how calmly one stands and faces death, jokes and laughs; everything is just an every day occurrence. You are mud covered, dry and caked, perhaps, but you look at the chap next you and laugh at the state he is in; then you look down at your own clothes and then the other fellow laughs. Then a whizz bang comes across and misses both of you, and both laugh together" (141).

Preliminary Action

On June 24, the Allied powers bombarded the German front lines with artillery. The barrage lasted a week and was intended to weaken enemy defences in advance of the July 1 ground attack.

Courtesy of the Rooms Provincial Archives Division (B-2-42), St. John's, NL.

At 9:00 p.m. on June 30, the Regiment departed Louvencourt and marched three hours to its trenches on the battlefield. "It is surprising to see how happy and lighthearted everyone is, and yet this is undoubtedly the last day for a good many," Steele wrote in his diary. "The various Battalions marched off whistling and singing and it was a great sight. Of course, this is the best way to take things and hope for the best."

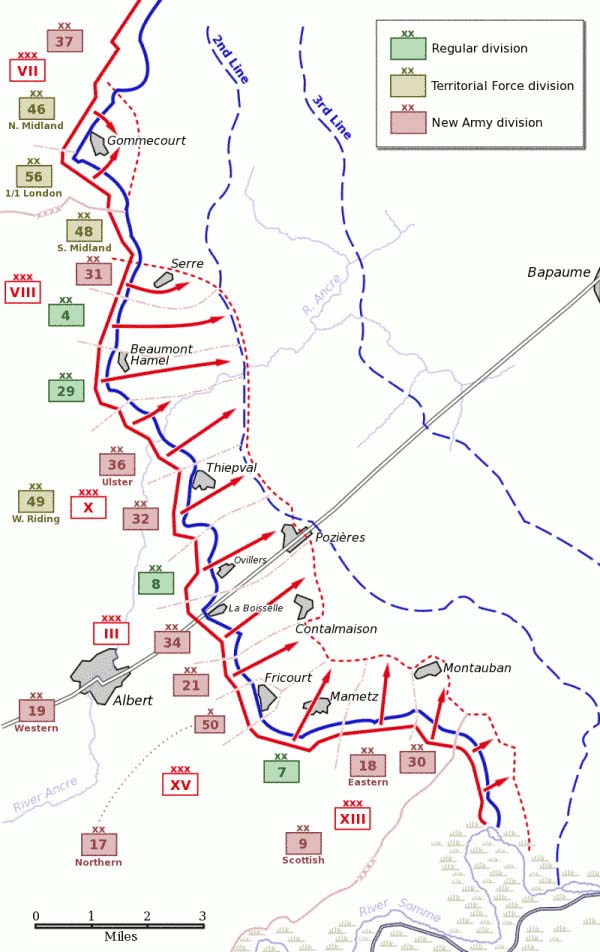

The battleground was a 34-kilometre ribbon of land near the River Somme. Allied trenches stretched along one side, and the Germans along the other. In between lay No Man's Land. The Germans held much of their front in great strength. They had created a three-tiered system of forward trenches, which was well dug in, shielded with extensive protective wire, and capable of surviving sustained bombardment. Beyond that, at ranges of between 2,000 and 5,000 metres, the Germans had constructed a second line of trenches and were working farther back on yet a third. This network of heavily defended lines presented a formidable obstacle to any attacking force.

Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons - http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:British_plan_Somme_1_July_1916.png#mediaviewer/File:British_plan_Somme_1_July_1916.png

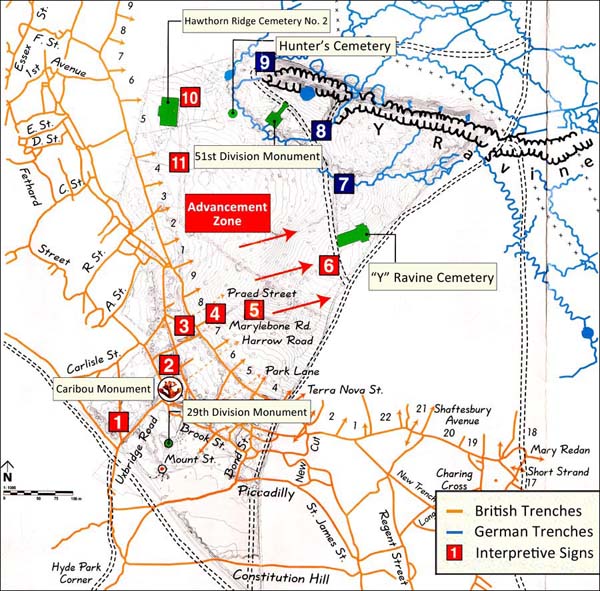

The Newfoundland Regiment was stationed in trenches near the French village of Beaumont Hamel, which lay behind German lines. It was a strategically difficult position. The German front lines were about 300 to 500 metres away, down a grassy slope and heavily guarded by barbed wire entanglements. The German 119th Reserve Regiment, tough and experienced, had turned the natural defences of a deep Y-shaped ravine into one of the strongest positions on the entire Somme front.

The Newfoundland Regiment's assignment (along with the rest of the 88th Brigade) was to seize control of the German trenches near the village of Beaumont Hamel. The Regiment would be part of a third wave of attackers to leave Allied trenches.

Zero Hour

The offensive began on the morning of July 1, 1916. At 6 a.m., Allied Forces bombarded the Germans with artillery for about an hour. At 7:20 a.m., they detonated more than 18,000 kilograms of explosives under Hawthorn Ridge. The ridge was an important German stronghold on its frontline, about 700 metres to the west of Beaumont Hamel. The blast turned the area into a giant crater, measuring 40 metres wide and 18 metres deep.

Photo by Ernest Brooks. Courtesy of the Imperial War Museums, (©IWM, Q 754), London England. http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205194574

In the preceding weeks, Allied commanders had debated whether to detonate the explosives four hours before the ground attack, two minutes before the attack, or at the very moment the soldiers left their trenches. A compromise set the detonation 10 minutes before zero hour. The timing was a terrible mistake. The explosion alerted Germans that a land attack was imminent, while the 10-minute delay gave them just enough time to strengthen their defences and ready their machine guns.

As the first wave of Allied troops left their trenches at 7:30, they were greeted by a devastating barrage of enemy artillery and machine gun fire. It was far stronger than anyone had anticipated. Most men were killed or wounded in minutes. A second wave of troops left their trenches soon after and met with the same fate. The Newfoundland Regiment was still in its trenches, awaiting orders to go over the top as part of a third wave of attack.

Courtesy of the Imperial War Museums (© IWM, Q 70164) London, England. http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205019092

By 8:00 a.m., there was considerable confusion along the Allied lines. The first two waves of attack had been devastating failures, but British commanders were receiving conflicting reports from the battlefield. Making matters even worse, divisional commanders mistook German flares for a signal of success from the attacking 87th Brigade. At 8:45 a.m., Brigadier-General Douglas Edward Cayley ordered the Newfoundland Regiment to advance "as soon as possible".

Newfoundland Regiment Advances

The men left their trenches at 9:15 a.m., with orders to seize the first and second lines of enemy trenches. But as they moved down the exposed slope towards No Man's Land, no friendly fire covered their advance. Instead, German cross-fire cut across the advancing columns of men, killing or wounding most of them before they even reached No Man's Land.

Private Anthony Stacey described the advance in his Memoirs of a Blue Puttee: "the wire had been cut in our front line and bridges laid across the trench the night before. This was a death trap for our boys as the enemy just set the sights of their machine guns on the gaps in the barbed wire and fired."(85)

Courtesy of the Rooms Provincial Archives Division (NA-2732), St. John's, NL.

There were other flaws in the Allied strategy. The weeklong bombardment that preceded the attack did not weaken German defences as much Allied commanders had hoped. Instead, it had the unexpected effect of leveling the landscape of No Man's Land, which deprived the advancing men of any cover from enemy fire.

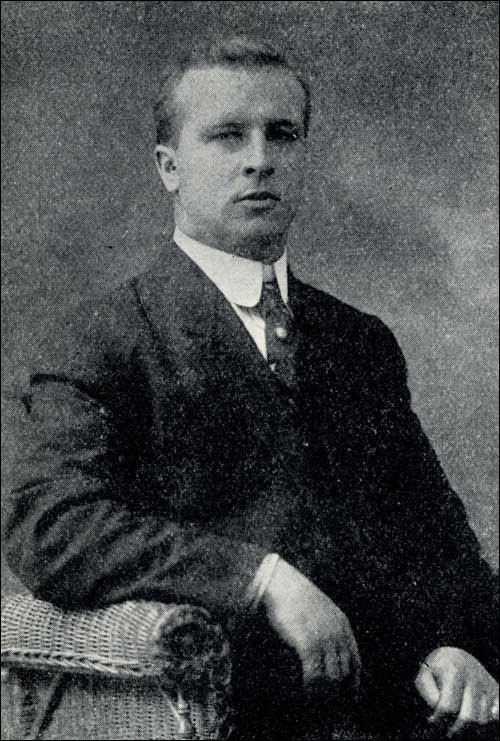

About halfway down the slope between the British and German trenches, however, a blasted apple tree did survive. Now known as the Danger Tree, it became a rallying point for the men of the Newfoundland Regiment who had made it into No Man's Land. But the tree provided meagre cover and the men became silhouetted against the sky as they approached it, making them easy targets for the German gunners. Many men died near the Danger Tree, including Private Francis Lind. He was 37 years old.

From The Book of Newfoundland, Volume I (St. John's, NL: Newfoundland Book Publishers, © 1937) 411.

The few men who did reach the German lines were horrified to discover that the week-long artillery barrage that preceded the attack had not cut the German barbed wire. Allied leaders had already obtained this information, thanks to a series of raids that reconnaissance teams had carried out in the nights before the attack. However, commanders had dismissed the reports, convinced that the raiders were inexperienced and the artillery bombardment much more effective than it actually was. As a result, the majority of the soldiers who reached the enemy trenches were killed, tangled in the uncut wire.

Attack a Failure

At 9:45 a.m., the Regiment's commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Hadow, reported to headquarters that the attack had failed. He received initial orders to gather any unwounded men and resume the offensive, but wiser counsel prevailed and the order was countermanded.

Throughout the day, survivors tried to make the long and dangerous journey back to their own lines, dodging enemy snipers and artillery fire. Private James McGrath lay on the battlefield for about 17 hours before he finally made it to safety.

Courtesy of the Rooms Provincial Archives Division (NA-6067), St. John's, NL.

"The Germans actually mowed us down like sheep," he later told the Newfoundland Quarterly. "I managed to get to their barbed wire, where I got the first shot; then went to jump into their trench when I got the second in the leg. I lay in No Man's Land for fifteen hours, and then crawled a distance of a mile and a quarter. They fired on me again, this time fetching me in the left leg, and so I waited for another hour and moved again, only having the use of my left arm now. As I was doing splendidly, nearing our own trench they again fetched me, this time around the hip as I crawled on. I managed to get to our own line which I saw was evacuated as our artillery was playing heavily on their trenches. They retaliated and kept me in a hole for another hour. I was then rescued by Captain Windeler who took me on his back to the dressing station a distance of two miles. Well, thank God my wounds are all flesh wounds and won't take long to heal up." ("Better than the Best," 5)

The attack was a devastating failure. In a single morning, almost 20,000 British troops died, and another 37,000 were wounded. The Newfoundland Regiment had been almost wiped out. When roll call was taken, only 68 men answered their names - 324 were killed, or missing and presumed dead, and 386 were wounded.

Courtesy of the Rooms Provincial Archives Division (VA 40-4.7), St. John's, NL.

The following days brought more fatalities. Lieutenant Steele had survived the Beaumont Hamel offensive only to be hit by a German shell on July 7 outside the regimental billets. He died one day later.

Link to Beaumont Hamel Guide Map Interpretive Signs Key.

Reaction

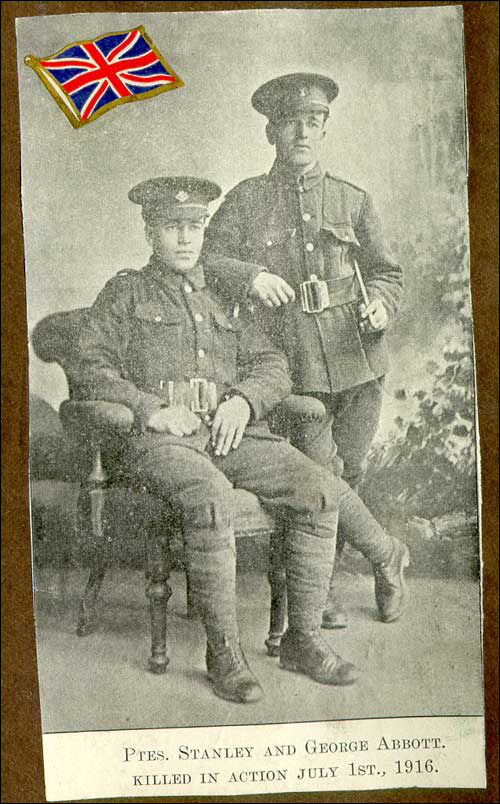

Beaumont Hamel plunged Newfoundland and Labrador into a period of mourning. Casualty lists appeared in local newspapers, but information came in slowly from the front lines and it was often incomplete. Many families had to endure a few tortured weeks of wondering whether their loved ones were alive or dead.

Courtesy of the Digital Archives Initiative, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John's, NL.

British officers sent letters of condolence to the many families who had lost sons, husbands, fathers, and brothers, and Allied leaders publicly praised the Newfoundland Regiment. Among them was Sir Douglas Haig, Commander-in-Chief of the British Forces: "Newfoundland may well feel proud of her sons. The heroism and devotion to duty they displayed on the first July has never been surpassed. Please convey my deepest sympathy, and that of the whole of our armies in France in the loss of the brave officers and men who have fallen for the Empire, and our admiration of their heroic conduct. Their efforts contributed to our success, and their example will live." (Evening Telegram July 21, 1916)

The first Memorial Day ceremony took place in downtown St. John's one year after the battle. In the 1920s, the Newfoundland government bought the ground over which the Newfoundland Regiment fought. The memorial park it established at Beaumont Hamel became a place of pilgrimage for people wishing to honour and mourn the Regiment.

Courtesy of the Rooms Provincial Archives Division (B 1-85), St. John's, NL.

Today, July 1 remains an official day of remembrance in Newfoundland and Labrador. Every year, people gather at the National War Memorial in downtown St. John's and at other locations across the province to remember the soldiers who fought at Beaumont Hamel, as well as the many other men and women who have served in other forces and other wars.

Lieutenant Owen Steele's quotes were transcribed from his diary: Collection 179, Archives and Manuscript Division, QEII Library, Memorial University.