The Railway Settlement Act & the Newfoundland Government Railway (1920-49)

After branch line construction was suspended in 1915, operating losses threatened the Reid Newfoundland Company. A post-war slump and a need to upgrade after years of deferred maintenance brought matters to a head by 1920, when losses topped $1 million. H.D. Reid informed the government that the company could no longer continue to operate the Railway.

Initially, the government and the company appointed a Railway Commission to operate the line for one year from 1 July 1920, raising $1.5 million for repairs and upgrading. It quickly became apparent that further capital was needed. Sir George Bury of the Canadian Pacific Railway was appointed to investigate, and recommended an arrangement whereby operating losses up to $1.5 million a year would be covered by the government, the remainder by Reid Newfoundland. In 1921-22 capital expenditures were kept at a minimum, while wages and schedules were cut drastically. The Bonavista, Trepassey and Bay de Verde branches were closed that winter, and there were no operations over the Gaff Topsail, cutting the main line in two.

In April 1922 Reid advised the government that even this curtailed, shared-risk operation was unacceptable, and from 16 to 23 May the railway was shut down completely. The government agreed to provide operating funds to July 1923, when it took over the railway through the Railway Settlement Act.

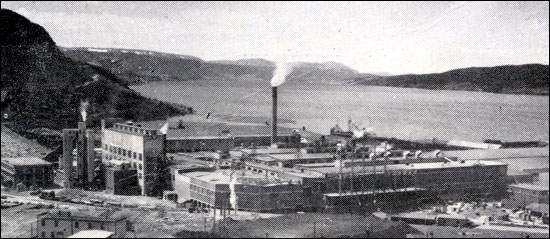

Under the terms of the act the government acquired the railway, coastal boats and dry dock from the Reid Newfoundland Company for $2 million, in recognition of additions and improvements made over the years. The company was forced to default on its operating contract, whereby the Reid lands would have reverted to the Crown. The explanation lay in the critical role the Reids and their lands were playing in the unfolding "Humber deal", which resulted in the opening of the Corner Brook pulp and paper mill in 1925. Indeed the timing of the Humber deal was central. Construction of the Corner Brook mill was announced in the spring of 1923, followed closely by an election, and then by the act.

Managing the Railway

From 1923 management of the new Newfoundland Government Railway (the name was changed to the Newfoundland Railway in 1926) came under the direction of a Board of Railway Commissioners, and the day-to-day management under general manager Herbert J. Russell (1890-1949). Russell had begun his working life with the railway and was Superintendent of the Eastern Division from 1917 to 1923. Russell's assistant was James V. Ryan (1894-1974), who had also begun with the Reids at the age of 16.

The new regime assumed management of nearly 1000 miles of track, including several branch lines which had no prospect of paying, and a main line which required complete re-railing. But by 1930, with a stringent regime of economy measures, the deficit was becoming manageable and new locomotives were ordered. Then the Depression brought near-disaster and a new round of wage cuts, layoffs, schedule reductions, and the closure of branches. After years of patiently paring the operating deficit, it leaped to $3 million in 1932.

Wartime Prosperity

The Newfoundland Railway did not begin to recover until 1936, when the construction of an airbase at Gander (of necessity wholly reliant on the railway) foreshadowed the central role the railway would play in the coming war.

After 1941 there was base construction at St. John's, Argentia and Stephenville, followed by an unprecedented volume of troop and material movements, coupled with a boom in civilian traffic. Under Lend-Lease, the Americans provided locomotives, cars, equipment and rails, Newfoundland (and its railway) being vital to the war effort in the North Atlantic. The U.S. Army also upgraded the Argentia line and terminal, and built a new branch to Harmon Field (Stephenville). It is ironic that, in its "finest hour," the Newfoundland Railway secured its enduring, mocking nickname, "the Newfy Bullet", from the Americans.

Unions Involved with the Railway

During the late 1930s the trade union movement took firm hold amongst employees of the Newfoundland Railway, with profound implications for the union movement in the country. For many railwaymen their first experience with unions had come during World War I, when a general union, the Newfoundland Industrial Workers Association (N.I.W.A.) flourished briefly. In 1927 J.V. Ryan had taken a leading role in founding a mutual benefit society, the Railway Employees' Welfare Association (R.E.W.A.). In 1934 the R.E.W.A. began the ambitious Own Your Own Home program, which eventually built 2,500 homes for railway workers at St. John's and Bishop's Falls.

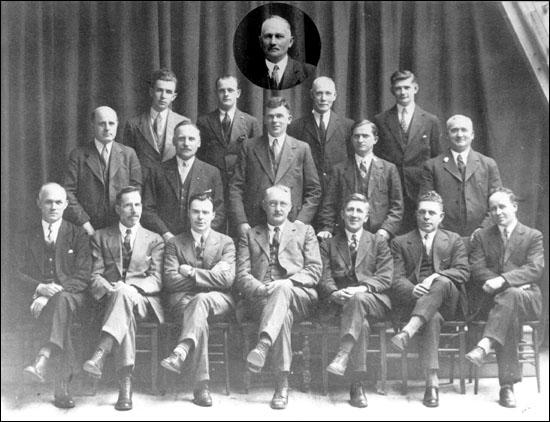

(L-R) First Row: W.J. Morrissey, W. Fogwill, J.V. Ryan, W.F. Joyce, T.J. Rolls, J.F. Pike, Capt. M.G. Dalton.

Second Row: E.D. Watson, H. Patrick, G. Cobb, M. Hawco, John Moore.

Third Row: G.C. Carew, R. Martin, D. Ferguson, C. Quick.

Top Centre: W.C. Harvey

In the early 1930s railway machinists and carmen were affiliated with international unions, but the drastic wage cuts of the Depression gave rise to a new push to organize, initiated by St. John's clerk Walter Sparkes, who established a local of the Brotherhood of Railway Clerks (B.R.C.). Sparkes and his co-workers were subsequently key men in organizing unions throughout St. John's and in the founding of the Newfoundland Federation of Labour in 1937. If Canadian organizers were astonished to find Newfoundland so highly unionized at the time of Confederation, it was largely the result of the commitment of the railwaymen not just to their own unions, but to the union movement in general. In October 1948, a strike by nine internationals shut down the railway for five weeks, the first system-wide strike since a 1918 strike against the Reid Newfoundland Company by the N.I.W.A.

At the end of the war, the Newfoundland Railway, from having operated in excess of capacity, needed upgrading and maintenance. From 1936 to 1946 the line had shown an operating surplus, but it now needed major work.