Indigenous Peoples in the First World War

Although people of Indigenous ancestry from Newfoundland and Labrador fought and sometimes died during the First World War, their histories remain largely unknown. Few documents and little research exist to describe their wartime experiences and motivations for enlisting. Because the country’s military records did not identify all Indigenous recruits, it is unknown exactly how many enlisted. It is also unknown how many died overseas due to enemy attack or illness.

Historians do estimate, however, that at least 15 men of Inuit and Southern Inuit descent joined the 1st Newfoundland Regiment. Most served in infantry units, which required the most soldiers, and many drew upon their hunting, trapping and other traditional skills to become expert snipers and scouts. Some were so proficient on the battlefield that they earned high praise and promotions from their superior officers, as well as military decorations from the United Kingdom and Canada.

Recruiting in Labrador

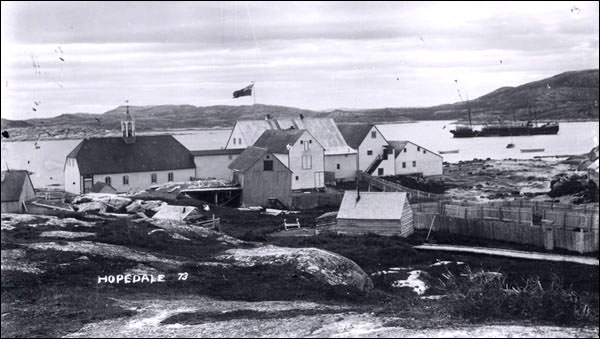

When hostilities broke out, most Indigenous people in Newfoundland and Labrador lived in isolated northern communities like Rigolet and Hopedale. News was slow to reach these areas and many residents did not immediately know their country had gone to war. Labrador’s remoteness and small, scattered population also meant recruiting efforts were initially confined to the island of Newfoundland. As a result, volunteering for military service was often more challenging for the country’s Indigenous peoples than it was for most other segments of the population.

Although the first contingent of 500 soldiers – mostly from St. John’s – left Newfoundland on 3 October 1914, the country still had to raise reinforcements for its regiment. To do this, many recruiters turned their attention to the colony’s isolated communities. On 20 June 1915, a sixth contingent of 242 recruits, known as “F” Company, departed St. John’s for Liverpool, England aboard the HMT Calgarian. Among this group were Inuit and Southern Inuit volunteers from Labrador.

The vessel, which was also escorting three submarines across the Atlantic, took the men past the Azores and Gibraltar before docking at Liverpool on 9 July. It was an exciting voyage for the new recruits, many of whom had spent all of their lives in small isolated communities. Shortly after disembarking at Liverpool, “F” Company moved to Ayr, Scotland, which was the regimental depot for most of the war. From there, some troops moved on to France, Italy, and other postings.

Military Service

Once overseas, many Inuit and Southern Inuit recruits became snipers or reconnaissance scouts with various infantry units. These were dangerous postings, which required great skill and stealth. Scouts slipped behind enemy lines to gather information about their opponents’ positioning and numbers, while snipers had to be expert marksmen, able to shoot distant targets from concealed positions. Most snipers worked in two-man teams consisting of a spotter, who observed and assigned targets, and a shooter.

The traditional skills of many Inuit and Southern Inuit recruits made them proficient snipers and scouts. John Shiwak, a hunter and trapper of Inuit descent from Rigolet, attributed his sniping prowess to his experience ‘swatching’ seals – a Newfoundland and Labrador term for watching the water and shooting seals as they quickly resurfaced to breathe. Shiwak, who sailed to England aboard the Calgarian, distinguished himself as an expert sniper while serving on the front lines in France; an unidentified officer reportedly called him “the best sniper in the British Army.” On 16 April 1917, Shiwak’s skills earned him a promotion to lance-corporal.

Although an expert and respected sniper, Shiwak quickly became depressed by the violence of war. In letters to his friend, Lacey Amy, Shiwak wrote of a desire to return home to his friends and family. Unfortunately, Shiwak died on the battlefield on 20 November 1917 after an exploding shell killed him and six other soldiers during the battle of Cambrai in northern France. He was 28 years old. Captain R.H. Tait of the Newfoundland Regiment called Shiwak a “great favourite with all ranks, an excellent scout and observer, and a thoroughly good and reliable fellow in every way.” Alongside praise from his fellow soldiers, Shiwak’s bravery and skill also earned him the British War Medal and Victory Medal.

Little is known of the other Inuit and Southern Inuit volunteers from Newfoundland and Labrador who fought in the First World War. Robert Michelin, a trapper of Inuit descent from Traverspine, served in France for two and a half years before sustaining a leg injury in the war; army surgeons told him he would likely not be able to hunt or snowshoe again. Frederick Freida, a trapper and hunter of Inuit descent from Hopedale, also served overseas. He returned home once hostilities ended, but maintained an interest in military service. In 1951, he joined the Canadian Rangers, a domestic reserve force in remote and northern communities.

John Blake, a volunteer of Inuit descent from North West River, also served with the Newfoundland Regiment. He suffered wounds in September 1918 during a battle at Ledeghem, Belgium, which later proved fatal (according to different sources, he may have died on 14 October or 14 December).

Alongside enemy fire, tuberculosis and other diseases also killed some Indigenous soldiers. This was most prevalent among volunteers from remote villages who became exposed to a variety of foreign viruses in the crowded trenches of World War One. It is unknown, however, how many – or if any – Inuit and Southern Inuit from Newfoundland and Labrador contracted illnesses because of military service.

After the War

Once hostilities ended, most surviving volunteers returned home to be with their families and friends. Many, like Frederick Freida, resumed their pre-war activities; others, like Robert Michelin, suffered injuries that interfered with their traditional ways of life. Occasionally, Indigenous troops were delayed in their return home because of the remoteness of their villages. This was the case with Michelin, who arrived at St. John’s in the fall, when there were no more steamers to Labrador until the following spring.

Returning soldiers often discovered their families and neighbours had not heard anything about the war for weeks, or even months, because of poor communication with St. John’s and other urban centres. Some residents at North West River, for example, did not know the war was over until returning veterans arrived there on 28 January 1919 – more than two months after the 11 November Armistice.