Response to the Ocean Ranger Disaster

The 1982 Ocean Ranger disaster exposed serious weaknesses in the way that government and industry regulated Canada's offshore industry. Inadequate emergency training, a flawed rig design, and poorly enforced safety regulations were crucial elements in the loss of 84 lives and the rig itself. Compounding the situation was a drawn-out struggle between the federal and provincial governments for ownership of offshore oil deposits, which distracted officials from putting in place a solid regulatory framework. Instead, the industry was managed by separate federal and provincial agencies, as well as the United States Coast Guard, resulting in an ineffective and needlessly complex bureaucratic structure.

The disaster forced government to quickly reorganize the industry and place a greater emphasis on worker safety. Ottawa and the province established a joint commission of inquiry on 17 March 1982 to investigate why the rig capsized and recommend ways to prevent future disasters. As a result of the commission's report, emergency training became mandatory, search and rescue equipment was upgraded, and rig design improved. A significant improvement was the consolidation of regulatory powers under a single entity, the Canada-Newfoundland Offshore Petroleum Board (today the Canada-Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Petroleum Board).

Royal Commission on the Ocean Ranger Marine Disaster

A month after the rig capsized on 15 February 1982, the federal and provincial governments jointly appointed a Royal Commission on the Ocean Ranger Marine Disaster. Chaired by Chief Justice T. Alex Hickman, the commission's mandate was to investigate three questions: why the Ocean Ranger sank, why none of the crew survived, and how similar disasters could be avoided.

Over the next two years, the commission interviewed witnesses, recovered and examined rig components, and conducted research studies. It published two reports, in August 1984 and June 1985. The first contained 66 recommendations dealing with the first two questions. The second made a further 70 recommendations on how to increase worker safety in offshore operations; it focused primarily on exploratory drilling, but also addressed the development and production stages.

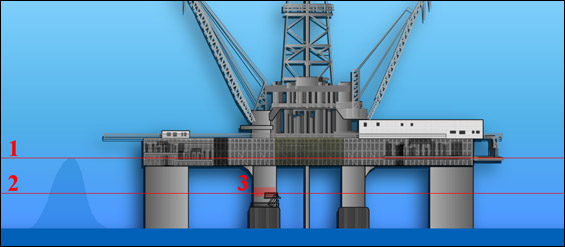

The commission found a number of factors contributed to the disaster - severe weather conditions, flaws in rig design, and the industry's inattention to worker training and safety. The rig had been built in the Gulf of Mexico and was not tested for the much harsher waters of the North Atlantic. The ballast control system (which controlled the depth and angle of the rig) was unnecessarily complicated and located too close to the water. Thin porthole glass could not withstand stormy waves, and chain lockers near the front of the rig were not watertight and vulnerable to flooding.

On the night of the disaster, a severe storm pounded the rig with hurricane-force winds and 15-metre high waves. Seawater broke through a porthole in the ballast control room and damaged equipment. The rig tilted forward and water flooded the forward chain lockers; it capsized in the early hours of 15 February 1982.

Compounding structural flaws were low standards for worker training. "For example," wrote the commission, "persons assigned to operate the ballast control system, which is critical to the stability of the semisubmersible, were not required by any regulation to have formal training." (Report Two, p. 71) No nationally recognized standards existed for safety training and government did not require industry to prove that employees were qualified for offshore work. Many workers learned through on-the-job training.

The commission concluded that a better qualified crew could have prevented the disaster: "Indeed, had the crew only closed the deadlights, shut off the electrical and air supplies to the panel, cleaned up the water and glass and then retired for the evening, the Ocean Ranger and its crew would have survived the storm that night." (Report One, p. 139)

Lifesaving equipment was also found inadequate and the crew lacked training in its use. No survival suits were onboard and lifeboats could not withstand stormy seas. The rig's standby vessel was the Seaforth Highlander, but it was not required by government or industry to keep a minimum distance from the Ranger. It was eight miles away when the emergency happened and did not arrive until the rig was evacuated. Its crew fought courageously to rescue survivors, but were untrained in lifesaving procedures and did not have access to important rescue equipment, such as safety lines.

The commission criticized the federal government's search and rescue response, particularly its reliance on 20-year-old helicopters it deemed ill-equipped for offshore sea operations. At the time of the disaster, these were stationed at Gander. The commission recommended that government or industry station a fully equipped long-range helicopter at the airport nearest to drilling operations (St. John's in the case of the Ocean Ranger).

Regulatory Shortcomings

At the root of many problems was the regulatory framework governing Canada's offshore industry, which was needlessly complex and failed to properly enforce existing guidelines. Three agencies governed the industry: the federal government through COGLA (Canada Oil and Gas Lands Administration), the provincial government through the NLPD (Newfoundland-Labrador Petroleum Directorate), and the United States Coast Guard. The US was involved because the Ocean Ranger was owned by American company, Ocean Drilling and Exploration Company, Inc. (ODECO), which Mobil Oil had contracted to drill the Hibernia field.

Both COGLA and NLPD assumed, but did not verify, that ODECO would comply with the US Coast Guard's regulations on marine safety, such as keeping qualified marine personnel and lifesaving equipment onboard and ensuring the rig was structurally fit for use. The Coast Guard did little to monitor the rig's compliance. In its second report, the commission recommended that a single Canadian agency regulate the industry, including drilling operations, the production of oil and gas, standby vessels, helicopters, and other rescue craft.

A longstanding dispute between Canada and Newfoundland for ownership of offshore resources further weakened the two governments' ability to impose a single and effective administrative system. As Canada sought to make the country a self-sufficient oil producer, and the provincial government focused on job creation for local people, worker training and safety became a secondary concern.

Government Response

The federal government responded quickly to the commission's reports and by July 1985 had acted on 90 of the 136 recommendations. Ottawa increased the province's search and rescue system to three fixed-wing aircraft and three helicopters, which exceeded the commission's recommendation for one. It also upgraded existing helicopters with long-range fuel tanks. Lifesaving equipment improved under new regulations from COGLA. Each drilling unit, for example, was expected to carry enough lifeboats and survival suits to accommodate twice the number of crew.

Standards for rig design improved and became more suited to the North Atlantic. These included changes to the ballast control room, which was elevated much higher above the waterline under COGLA regulations. COGLA also decreased the complexity of ballast control systems, put in place greater safety mechanisms, and required all operators to have formal training.

Training became heavily regulated, for both work and safety skills. Industry cooperated with the provincial and federal governments to develop a standard level of competency and safety training for all offshore workers. These are updated regularly and extend to personnel on standby vessels as well as drilling rigs and production installations.

A major change was the creation of the Canada-Newfoundland Offshore Petroleum Board in 1985, later renamed Canada-Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Petroleum Board (C-NLOPB). It replaced COGLA, NLPD, and the US Coast Guard as the single regulatory agency responsible for the offshore industry. The Offshore Petroleum Board was established under the 1985 Atlantic Accord between Newfoundland and Canada, which settled a drawn-out dispute over ownership and management of offshore oil and gas. Although the establishment of the Offshore Petroleum Board was not a direct result of the commission's reports, the disaster placed considerable pressure on Ottawa and the province to resolve the conflict quickly.

Criticisms

Although the Ocean Ranger disaster sparked much positive change, government and industry have also been criticized for not doing enough. Change was swift in the first few years after the disaster, but then slowed. A 2006 report commissioned by Transport Canada found that research into escape, evacuation, and rescue (EER) decreased in the 1990s and regulations failed to keep pace with technological advancements: "It has, unfortunately, been demonstrated that regulatory development, much like the EER technology research, generally keeps pace with the last major disaster. Prescriptive regulatory requirements put into place to respond to specific needs are generally appropriate at the time, but are rapidly overtaken by technological progress." (Leafloor 29)

Others criticize the government for its slowness in legislating regulations into law, or for failing to fully implement all commission recommendations. It was not until 1992, for example, that the House of Commons passed the Canada Oil and Gas Operations Act. C-NLOPB and industry officials insist all regulations are being followed as though they have the force of law.

Government compliance with the commission's reports was again questioned in 2009, after a Cougar helicopter crashed into the Atlantic Ocean on 12 March while bringing workers to the White Rose and Hibernia oilfields. Seventeen people died. Although the Commission recommended that a search and rescue helicopter be stationed at the airport nearest to drilling operations, all were in Nova Scotia on a training exercise at the time of the crash. The tragedy again highlighted the hazardous nature of the offshore industry and the importance of the work done by the commission in the wake of the Ocean Ranger disaster.