Lundrigan-Butler Affair

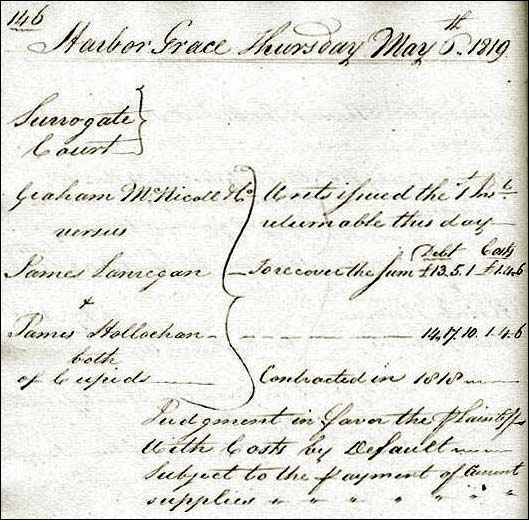

In 1820 Newfoundland witnessed perhaps the most important cause célèbre in its history. The affair centred on the cases of two Conception Bay fishermen, James Lundrigan and Philip Butler, who were publicly whipped after receiving default-judgements in surrogate court for outstanding debts. In 1818 Lundrigan had borrowed around £13 from a local supplier and, when the surrogate court met the following year, the merchant brought an action to recover the debt. The court ruled against the fisherman, whose property was attached, but Lundrigan and his wife, Sarah, successfully resisted efforts to take possession of their house.

Courtesy of The Rooms Provincial Archives Division (GN 5/1/B/1), St. John's, NL.

Summoned to appear before a surrogate court in July 1820, Lundrigan refused on the grounds that he had to go fishing to feed his hungry family. Arrested during the night, he was taken to a naval vessel, charged the next day with contempt of court and resisting arrest, and sentenced to receive 36 lashes on his bare back. Lundrigan, who was an epileptic, collapsed after 14 lashes, and a surgeon stepped in to stop the whipping. The court ordered Lundrigan to relinquish his house and assets to his creditor, thereby evicting his wife and four children.

Philip Butler's case, which took place the next day, followed a similar course. An indebted fisherman, Butler was sentenced to receive 36 lashes for contempt of court (he was given 12), and he and his family were also evicted from their home. Supported by a group of reformers in St. John's, both Lundrigan and Butler took actions of trespass in the Newfoundland Supreme Court for assault and false imprisonment against the presiding surrogate judges.

The reformers turned the cases of Lundrigan and Butler into a serious political issue. In 1820 they convened a meeting to protest against the cruel punishments inflicted for minor offenses. Chaired by Patrick Morris, the meeting included many of the leaders of the Catholic community who formed the backbone of Newfoundland's reform movement; the fact that Lundrigan and Butler were Irish only served to underscore the deep concerns among Catholics over the island's legal system. A committee was appointed to draft a petition to London. In addition to detailing the flaws in the surrogate system, the petition linked directly the need for a civil judiciary to the absence of local legislature. Stressing the reformers' patriotism and allegiance to the king, it appealed for all the rights and privileges granted to British subjects in other British colonies.

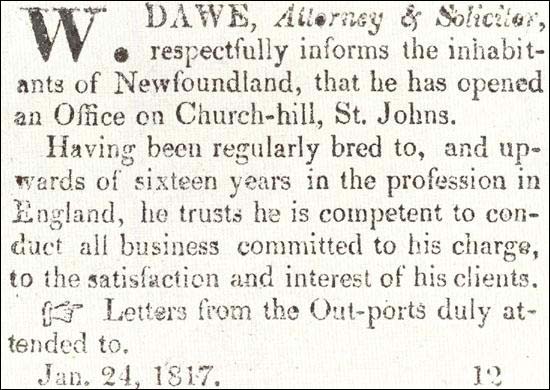

The committee sent a representative, William Dawe, to convey the petition to England. Dawe also carried letters asking prominent politicians to represent the reform committee's interests in parliament. When the House of Commons considered the petition in 1821, Sir James Mackintosh asserted that he knew of no other colony which required the constant vigilance of a local assembly more desperately than Newfoundland. The British government admitted that the island's judiciary required an overhaul, but warned of the problems associated with colonial assemblies. The Colonial Office had, in fact, already informed Governor Hamilton that it had no intention of granting Newfoundland a legislative assembly.

From the Newfoundland Mercantile Journal, January 24, 1817. Courtesy of the Archives and Special Collections, QE II Library, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John's, NL.

Undaunted, the St. John's reformers organized a public meeting to place their case before a wider audience. Held in August 1821, the meeting established the principal arguments for representative government. Patrick Morris recounted how the island's long history of oppression under English merchants and naval officers had produced a legal system unequaled in the annals of despotic nations. Not only did the absence of a properly-constituted civil judiciary deny settlers recourse to British justice, but backward laws also prohibited exploitation of the island's agricultural resources and thus retarded economic development. The absence of electoral representation deprived Newfoundlanders of their constitutional birthrights as British subjects. Newfoundland was left to endure taxation without representation, while its revenues were ample to support a legislature. The committee concluded that all these problems were, at bottom, caused by the want of an elected assembly.

Any doubts over how the reformers intended to use the Lundrigan-Butler case were removed by their publication of a lengthy report in 1821. As its preface made clear, reformers viewed the incident as an opportunity to generate public support for their great struggle against oppression:

The following pages contain an account of the trial and punishment of BUTLER and LANDERGAN [sic]—cases which are too well known in Newfoundland to be readily forgotten, and which are now published from no vindictive feeling, but merely as they are connected with the proceedings to which they gave rise, and may hereafter be conducive to the public good. It has been well observed by a popular writer, that the flagrant abuse of any power in England always produced re-action, which either demonstrates that power to be contrary to the constitution, or by an expression of public feeling restrains it for the future. The oppression of an obscure individual was the cause of the famous habeas corpus act: the unjust punishment of two poor Planters in Newfoundland may have the effect of raising the people to a level with the other colonists of North America, and securing to their posterity the invaluable privileges of British subjects (Anon. 1821 iii).

By placing the Lundrigan-Butler affair in the context of the historic struggle for British justice, the reformers sought to raise the political stakes higher than just a debate over the surrogate courts.

Painting by William Beechey. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

These efforts began to pay off in 1823, when the British government announced plans to amend the laws governing Newfoundland. Patrick Morris traveled to London and, after meeting with officials, published a pamphlet in 1824 calling for an end to naval government. The Colonial Office was receptive to law reform but maintained that Newfoundland was not yet ready for a local legislature because of its backward social development. Still, the Judicature Act of 1824 and the Royal Charter of 1825 included a series of important measures: official colonial status and a civil governorship; abolition of the surrogate courts; introduction of a system for land grants; and provisions for a charter of incorporation empowered to make town by-laws. Although the Royal Charter did not provide for an elected assembly, reformers considered it a major victory. After more than a century, the Royal Navy no longer controlled the island's government or participated in its judicial administration. The Lundrigan-Butler case was not only a turning point in the history of law reform; over time it became part of Newfoundland's cultural memory as a powerful symbol of resistance to oppression.